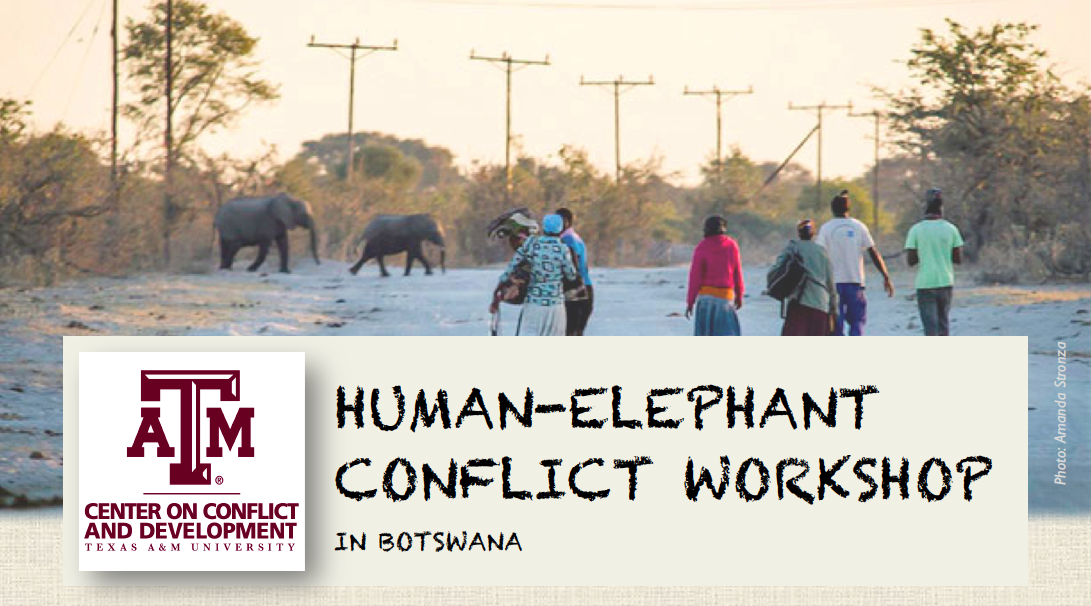

ConDev teamed up with Ecoexist and MIT’s D-Lab for a five-day workshop in Botswana to engineer solutions that foster coexistence between humans and elephants in the country’s Okavango Delta. This workshop brought together local farmers and students from Texas A&M, MIT, and the University of Botswana. Get the full field report here!

ConDev teamed up with Ecoexist and MIT’s D-Lab for a five-day workshop in Botswana to engineer solutions that foster coexistence between humans and elephants in the country’s Okavango Delta. This workshop brought together local farmers and students from Texas A&M, MIT, and the University of Botswana. Get the full field report here!

Here’s a first-hand perspective from program participant Abin: “Breathless in Botswana”

“It’s not real until the plane is in the air.” I thought to myself.

My aisle seat shook as our 747 taxis on the tarmac at Bush Intercontinental Airport. It was 3:05 pm, 90 degrees Fahrenheit in Houston, we were going 120 miles an hour and just like that- the wheels were off the ground. It was only then that I allowed myself to celebrate as much as I could without disturbing the kind Ukrainian man seated beside me. Up until then, I held my breath because I could’ve sworn it was all a dream.

Two months prior, I was interning as an engineer in the kind of office that considers cereal as a snack break. I stared at sketch models and visualized my upward mobility in this business, imagining my cubicle walls growing into a full blown corner office. Although fully aware of my good fortune with this opportunity, I felt as though, if given the chance, I would trade my seat for one in the sky headed somewhere far from here. I wanted to go somewhere I could make a real difference.

That’s when it happened.

The Program on Conflict and Development (ConDev) was searching for students to travel and work in Botswana, and when I heard about this opportunity, I knew it was exactly what I was looking for.

None of it felt real – the application acceptance, meeting with the team I’d be working with – it all felt like a dream. Yet, once the wheels lifted off the ground, reality finally set it. I was really doing it. I promised myself that I’d make every second count.

ConDev brings together university innovators with field practitioners to solve problems in conflict areas. Our particular mission was to co-create innovative solutions with farmers in the Northern Panhandle of Botswana, in order to mitigate human-elephant conflict that plagues the region. We would be working with an impressive group of people during our time there: Ecoexist was our local partner for the expedition and organized the farmers’ participation through their long standing work in human-elephant conflict in the region.

Amy Smith and MIT’s D-Lab provided the framework and facilitation of the workshop for the group. The idea behind the workshop was to equip the local residents with the skills and tools to engage in problem solving through the dissemination of the engineering design process. Students from the University of Botswana were also recruited to participate and were chosen by winning a competition held by Ecoexist on creating relevant and innovative solutions for conflict mitigation. By bringing together people from all over the world, we enhanced the creative process by merging vastly different perspectives.

Everyone of the participants came eager to find solutions. Data doesn’t have a voice, or a face or dreams, or mouths to feed back home. As I stepped foot onto this new continent, I collected my luggage but left my preconceived notions back in the cargo.

At camp, we joined the rest of the participants and broke off into smaller, specialized teams. My introduction to my group was full of song, dance, and cultural immersion. It was very exciting, but not easy by any means. I could tell that the cultural barrier was initially present; the discrepancies in nonverbal communication made it difficult to speak with the farmers without a translator. Nevertheless, little by little, I recognized more similarities between us than differences. A smile and a laugh meant the same thing to them as it does to me. The older women were leaders of the dances in their villages, and given the chance, I’m sure we would have torn up the dance floor together. The most resounding similarity between us, though, was their passion and commitment to making the most out of the workshop.

Our team’s goal was to improve the current method of millet farming with a holistic approach to conflict mitigation. The women farmers were most eager to work on this issue. As they invited us to the local village for a demonstration of their current process, I decided to ask them about their interest working on millet farming problems. Motombo, one of the elders in our group, responded with one of the great truths of Botswana: women were responsible for every stage of the millet life cycle, from planting the seeds to preparing the meal. I had no idea how much responsibility rested at the feet of the women of the community.

The women led me into their homes and their lives, not hesitating to share their perspective, demonstrating the physically arduous tasks of their daily lives. After all, they were responsible for their family’s well being. For hours on end women repeatedly beat fingers of millet, with song and dance to combat its tedium, to have enough food for their families. Subsistence farming was defined for me that day; I now understood that if they don’t work as hard as they do, they don’t eat.

The women worked very hard, and we wanted help them get better results for their investment. There was room for improvement when it came to efficiency during any of the laborious stages of millet farming. After taking a poll, we decided to focus on improving the most physically strenuous aspect, which was the thrashing, or removing of seed from millet fingers. Brainstorming solutions didn’t take long at all because everyone was contributing and engaged. Soon we had enough information to start building our prototype. The Botswanan farmers had the creativity and desire to solve their problems, but lacked some of the tools and knowledge about the design process. They were vocal about this shortcoming and I felt as though I had witnessed one of the silent injustices of the world. Despite any adversity they faced, these farmers returned each day with the same level of enthusiasm.

Even with a child strapped to her back, Kavundo sat with us daily and helped innovate a better way to thresh millet. Being eight months pregnant did not stop Tslano from carving out a working prototype from raw and local materials in a day and a half.

Our prototype wasn’t flawless, but it worked, and most importantly: it was ours. Where nothing existed a day before, there was something. As we displayed our millet thrasher, on another display was the pride of creation, a story told through each of our faces. Our workshop might have been over, but our story wasn’t.

We parted ways the following day and they thanked me for all of my efforts to make their lives better, yet I was the one overflowing with gratitude. The dream was over, but it was never really a dream. It was real.

My aisle seat shook as our 747 on the way back down. It was 8:45 pm, 85 degrees Fahrenheit in Houston; we were going 150 miles per hour when we landed on the tarmac at Bush Intercontinental Airport. I started to hold my breath again.